The Age of Inquiry

In March, 1827, Freedom’s Journal, the first black-owned and operated newspaper was established with the goal of reaching the free black population in the northeastern part of the U.S. A speech (delivered in July, 1830) by one of its founders, Peter Williams, is among some of the earliest speeches held in the Black Abolitionist archive.

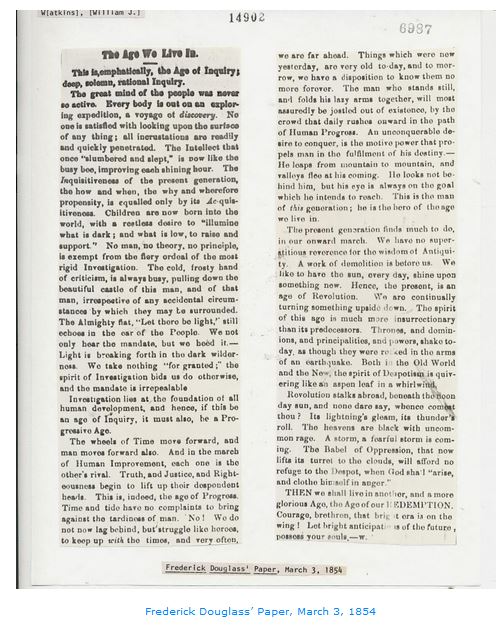

Soon, other black-owned newspapers followed. Among these was Frederick Douglass’ Paper (which had evolved from his previous newspapers), and among the editors of this paper was teacher, writer, and Black Abolitionist, William J. Watkins.

One of the things that makes the Black Abolitionist archive unique is the collection of editorials and speeches by writers who may not be as well known as men like Frederick Douglass. William Watkins is one of them. Although he wasn’t born into slavery, he identified strongly with the plight of those who were. He lived during one of the bleakest periods in American history, and, through sheer determination and a powerful intellect, he became a compelling voice for justice that guided an entire race of people through that horrible time.

“The Age We Live In” (included here) is a great example of Watkins’ work. In it, he describes his generation as the “age of inquiry and investigation.” He saw among his people a renewed interest in education, research, and betterment. He viewed his time as a “revolution” of progress and enlightenment; and so it was in many ways.

William J. Watkins lived between around 1803 to around 1858. When historians speak of these years, they tend to focus on the horrors of slavery and the way the country’s economy grew on the backs of the enslaved portion of its population. But behind the scenes progress was taking place, encouraged and inspired by writers, editors, and journalists working with the power of the written word for the cause of liberation for all. These were the heroes of this time. These were the men and women who fought tirelessly for the cause of freedom. Among these, William J. Watkins stands out as one of the most eloquent and outspoken. His name has slipped into the cover of history. This current “age we live in,” however, may be the perfect the time to re-introducing him to the world.

Contributed by Linda Papa, Digital Technician