Colonization is the process by which one power dominates another. This can be the way a more powerful country takes control of another, but it’s also the way one culture seeks to control another by usurping the established cultural civilization of another. This has happened time and again since human beings migrated out of Africa — as they defeated tribes and gained territories, as they morphed languages and destroyed religions, they also changed their own culture. Societies have evolved by snuffing out the weaker cultures, and taking control of their languages, their rituals, the details of their social structures that made the conquered culture unique.

During the bleak early years of this country’s development, one race dominated a captured other (not just Africans but also the native peoples). To complete this domination meant removing all traces of the captured race’s culture: language, dress, rituals, religion, and social structure. With this, the dominate culture would guarantee that the children of these captured peoples would no longer pass along the heritage of their own culture. The power held in the unique expression of this dominated culture would be merged with the dominate race and thereby rendered powerless.

One problem of this form of domination was adjusting to the potential outcomes of change once the dominated culture had been absorbed. The question the dominant culture asked during slavery was, “What are we going to do with the free people of color? How do we absorb a race that looks so different from us without changing who we are?”

One answer to this problem was in colonizing the original country. The idea was to return the freed people of color to Africa as representatives of change, never mind that most of these people had been born into the dominant culture. Never mind that they had never known life in Africa before this time. For the dominant culture, this seemed like a good solution: remove those “others” who don’t look like us now that the culture has been conquered.

This line of thinking is similar to that of those in power today who believe deportation is the best cure for the problem of too many illegal immigrants in this country. Return them to their country of origin, no matter what their current experience is.

Colonization of Africa was supported by many black leaders during this time. It seemed like a good idea. The notion of spreading Christianity to the “heathens” and rescuing the Godless from themselves was seen by many as a worthy cause. Others found the idea of establishing a government similar to that of the U.S. would be beneficial to African tribal communities that were viewed as uncivilized and little more than bands of savages roaming a chaotic and dangerous continent. This idea was sold as a benefit for all concerned. And any natural resources we could glean from Africa in the process were justified by our assistance in saving them from the inherent evil of themselves.

A major proponent of Colonization was a black abolitionist named Alexander Crummell. Crummell was a prolific writer and dedicated abolitionist. He worked hard to promote his idea of a unified African racial presence in the U.S., as well as in Africa. He worked tirelessly to assist those who were so poorly treated in this country by moving as many people as he could to realize true freedom in the country of their ancestry. As this idea came together, Crummell was instrumental in the establishment of a government in Monrovia, Liberia, to bring about major social change for the free people of color.

Alexander Crummell’s wiki page tells us that he was born in New York City, and through the sponsorship of prominent abolitionists in England, attended Queens College at Cambridge. His parents instilled in him a strong affinity with all people of color, and a special connection with Africa. We also learn the following from his wiki page:

“During his time at Cambridge, Crummell continued to travel around Britain and speak out about slavery and the plight of black people. During this period, Crummmell formulated the concept of Pan-Africanism, which became his central belief for the advancement of the African race. Crummell believed that in order to achieve their potential, the African race as a whole, including those in the Americas, the West Indies, and Africa, needed to unify under the banner of race. To Crummell, racial solidarity could solve slavery, discrimination, and continued attacks on the African race. He decided to move to Africa to spread his message.”

Crummell’s intentions were sincere and based on solid ideas he had formed while studying at Cambridge. These ideas looked great “on paper,” but the human element wasn’t considered carefully. Those who opposed Colonization fought just as hard to stop it. People of color born in this country had no desire to be uprooted and moved to a totally alien place. In addition to this, it wasn’t long before proponents discovered that the government structure that worked well here, unfortunately didn’t work as well in Liberia. And then there were the logistics: how do you move people in this fashion?

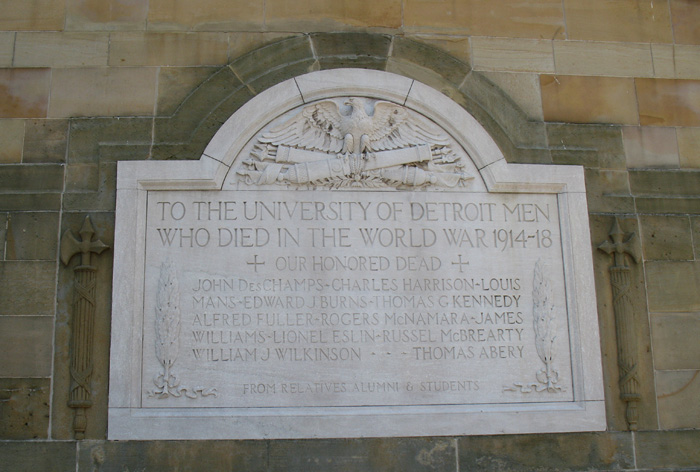

Opposition to Colonization was strong. And while it succeeded in establishing the city of Monrovia in Liberia (named after president James Monroe) and the university there, the dream didn’t manifest as it had been dreamed.

Alexander Crummell’s wiki page also offers the following:

“Crummell was an important voice within the abolition movement and a leader of the Pan-African ideology. Crummell’s legacy can be seen not in his personal achievements, but in the influence he exerted on other black nationalists and Pan-Africanists, such as Marcus Garvey, Paul Laurence Dunbar, and W. E. B. Du Bois. Du Bois paid tribute to Crummell with a memorable essay entitled “Of Alexander Crummell”, collected in his 1903 book, The Souls of Black Folk.

In 2002, the scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Alexander Crummell on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[10]“

The University of Detroit Mercy is proud to offer 28 of Crummell’s writings and speeches in our Black Abolitionist archive. This man’s legacy is an amazing testament to the work of so many abolitionists in their struggle for social freedom.

Contribution by Linda Papa, Digital Technician

Contribution by Linda Papa, Digital Technician